In Bolivia, gains in school attendance have not reduced poverty or income inequality.

Our case study ‘A country at risk of being left behind: Bolivia’s quest for quality education’ found that the education children and young people are receiving does not allow them to access decent work in the labour market. Furthermore, ethnicity and gender still shape children’s ability to benefit from quality schooling.

Highlights

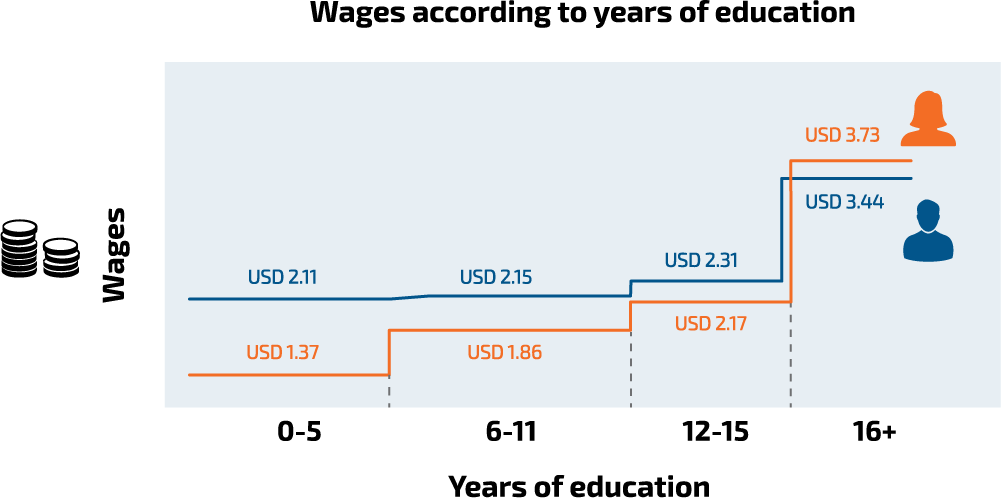

For young men in Bolivia, the first 15 years of education do not result in significant wage increases.

For those completing the first three education levels (0–5 years, 6–11 years, and 12–15 years), their wage distributions are almost the same. This means that completing 12 to 15 years of education mostly just helps a young man avoid extremely low wages, rather than providing further benefits.

In the case of women, education returns were almost twice as high than in the case of men. However, women generally earn less than men at all levels of education.

Gaps in accessing education for ethnic minorities have been steadily closing in Bolivia. By 2017, virtually all children, irrespective of ethnicity, attended both primary and secondary school. But children from ethnic minorities are still more likely to repeat a school year than children from mestizo background.

Students who speak Spanish are generally more likely to go to school than those who speak Aymara or Quechua.

Quechua speakers are the slowest to start school, with less than 50% of 5-year-olds in pre-school in Bolivia. They were also the most likely to drop out.

Lykke E. Andersen

Lead ResearcherLykke is Executive Director of the Sustainable Development Solutions Network in Bolivia. She is the highest ranked economist in Bolivia, and among the top 5% of female economists in the World (according to RePEc).

Werner Hernani L.

Lead ResearcherWerner holds a master’s degree and a PhD in Economics from the University of Pennsylvania. He is the co-founder of Fundación ARU and has advised research and policy decisions in more than 35 countries across the developing world.

Agnes Medinaceli

Junior ResearcherAgnes holds a BA in Economics from the University of St Andrews and a master’s degree in Latin American Development from King’s College London. She has worked as a consultant at INESAD, SDSN Bolivia, and Fundación ARU.

Carla Maldonado

Research AssistantCarla holds a BA in Economics from the University of San Andres in Bolivia and is currently studying Mathematics at the same university. Before working in Fundación ARU, she worked at the Ministry of Economics and Finance as a junior analyst.