This policy brief calls for a rethink of the social contract in Latin America, to tackle the redistribution of power…

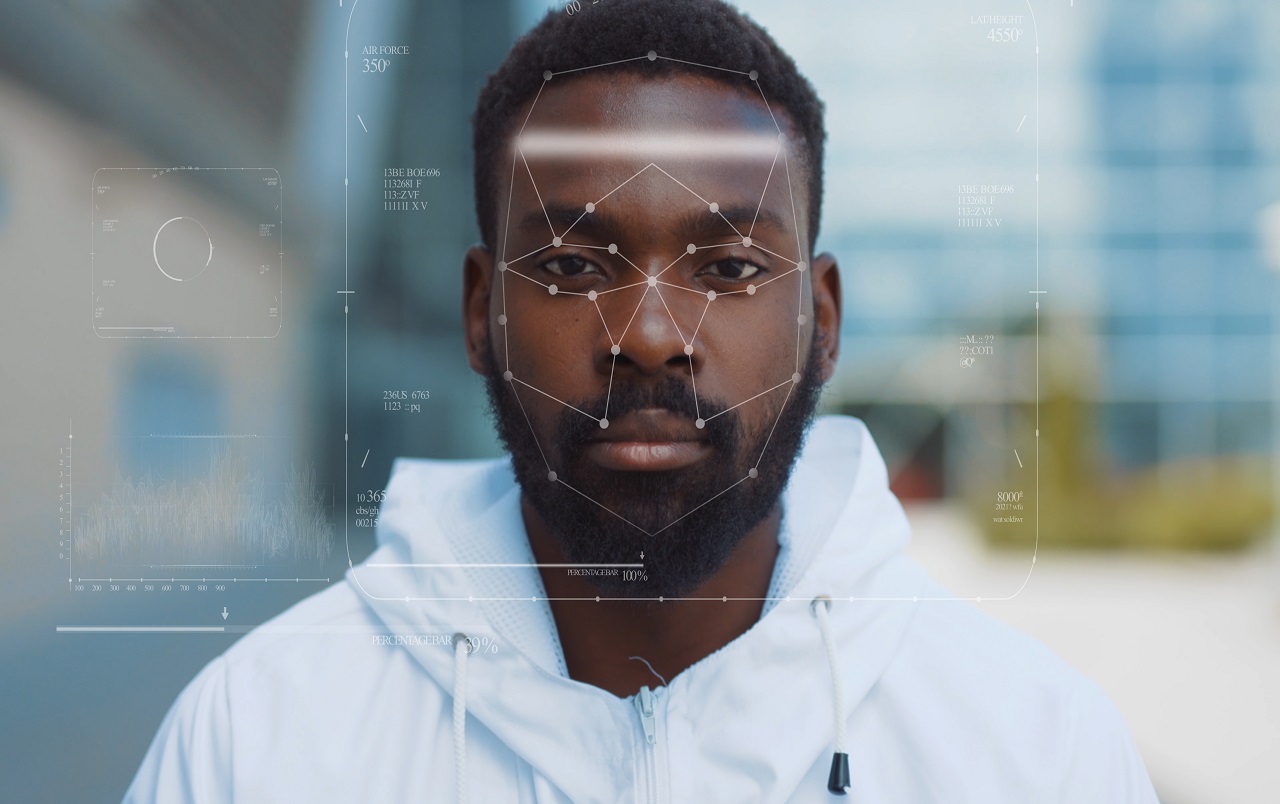

“A promise of better security, an innovative improvement of public policies, or a solution for social conflicts”. These are often the justifications for monitoring and surveillance technologies, such as cameras and facial recognition software.

Yet, in Brazil and other contexts marked by extreme racial, ethnic and gender inequalities, such technologies can backfire. Historically marginalized groups are more exposed to mistakes made by such mechanisms. Additionally, these technologies can be used as a tool for community control – increasing violence, hypervigilance by state actors and judicial bias in criminal proceedings.

Despite warnings by experts about its risks and discriminatory consequences, public security agencies’ adoption of this type of technology is increasing significantly in Brazil. In the State of Rio de Janeiro alone, 80% of people affected by facial recognition identification mistakes are black. Still, in January 2022, ignoring the risks of adopting this type of technology, the State Secretariat of the Military Police of Rio de Janeiro decided to install 22 facial recognition cameras near the community of Jacarezinho, a region already marked by significant police violence.

It is part of a broader context of a series of security measures introduced by the State of Rio de Janeiro. In theory, the plan encompasses social services and infrastructure improvements for the communities. In reality, the initiative replicates the model of military occupations in predominantly black and low-income regions with disastrous consequences. The program is inspired by no less than a failed intervention called Pacifying Police Units (UPPs), which was established in 2014 ahead of the World Cup and the Olympics in Rio de Janeiro (2016). It was implemented in 2018. During this period, the power of the Armed Forces in the intervention and control of the urban space in Rio increased significantly.

The beginning of “predictive policing”?

In a 2022 study by the Panopticon project, researchers found that the term of reference presented by the State of Rio de Janeiro has methodological gaps. For example, the absence of the execution period and a lack of dialogue with the residents, in addition to arbitrariness regarding the right of access to the images produced by the cameras. It serves only as a repressive use of police power and strengthens the production of evidence to support police innocence in trial settings. The data is not made available to eventual victims of excesses in the use of violence and human rights violations by the historically repressive state security forces.

Therefore, testing such technologies in places like Jacarezinho reflects the determination of the Public Authorities in the so-called “war on drugs”. Jacarezinho is a favela that, in May 2021, experienced the biggest massacre in the history of Rio de Janeiro, with 28 deaths resulting from a police incursion amid the Covid-19 pandemic.

The use of facial recognition could open the door to the beginning of predictive policing. It is when security interventions are planned based on predictions made by commonly biased algorithms – a practice already frequent in the United States. Brazil is marked by spatial segregation and repressive monitoring of the black population and the working class. So, this type of precedent challenges fundamental rights such as the presumption of innocence and exercising the right to protest.

Likewise, strictly technological solutions do not consider a structural problem that also affects the development of surveillance technologies: racism. According to the 15th Brazilian Public Security Yearbook, in 2020, 66.3% of people incarcerated in the country were black. Out of the 6,416 victims killed by police forces that year, 78.9% were black.

Increased stigmatization

Racism is thus expressed as algorithmic racism when biased data and programming – responsible for feeding artificial intelligence mechanisms – are predisposed to single out a group of people as more prone to committing crimes. In this case, it would be black people. It is a clear violation of their right to presumption of innocence.

Several Brazilian organizations, campaigns and experts have mobilized to curb the use of such technologies. For example, the Take My Face Out of Your Aim campaign seeks to ban facial recognition for public security purposes. At a global level, the Campaign to Stop Killer Robots seeks to prohibit the development of lethal autonomous weapons, which use sensors and facial and voice recognition mechanisms to select and fire against targets without meaningful human control.

It is essential to stop security operations and activities that are based on technologies with high discriminatory potential. They enhance the ability of the State to harm human dignity and threaten human rights. The decision on who should be considered a suspect or remain at liberty cannot be delegated to machines.

Text editor: Gabriela Keseberg Dávalos