This article highlights some of the key findings of a new study on the impacts of COVID-19 on Sri Lanka’s and Bangladesh’s apparel sector. The text focuses on factory workers in Sri Lanka and how to protect them better in future crises.

Sri Lanka’s apparel exports fell by 27.6% compared to the previous year. This change was due to an unprecedented confluence of supply and demand-side disruptions caused by the pandemic. Even though the industry experienced a marginal recovery during the second half of the year, it continues to be affected by regular disturbances of the second wave of COVID-19. These effects are especially tough for the nearly 350,000 employees dependent on the industry.

Workplace Safety, Complacency, and Regulatory Gaps

Amidst an almost complete halt in production during March and April 2020, Sri Lanka’s apparel sector began its recovery in the following months. Workplace health and safety guidelines established by the government were relatively effective in protecting factory workers from the pandemic during the first wave. While regional neighbours, such as Bangladesh and India, reported numerous clusters of cases within the industry between May and August, there were no COVID-19 cases associated with apparel factory workers in Sri Lanka during the same period.

However, scrutiny in Sri Lanka regarding workplace guidelines enforcement, both at factories and other public spaces across the country, relaxed in August and September. Many of our interviewees noted that public messaging in the absence of COVID-19 community transmission created a sense of complacency. It led to a general lack of vigilance. It was later identified as a significant catalyst for the second wave.

The pandemic exposed a gap in Sri Lanka’s labour laws. It could potentially undermine the response to workplace safety during COVID-19 in the medium term. In general, the Department of Labour has investigated violations in working conditions and other labour-related issues through the Factories Ordinance and the Shop and Office Act. Yet, since the coronavirus outbreak, the National COVID-19 Taskforce and the Ministry of Health have issued all regulations and work requirements.

Thus, the Department of Labour investigators have no powers to inspect any COVID-19 related violations at the workplace. Instead, these particular regulations’ investigatory powers lie with Public Health Inspectors (PHIs) and Ministry of Health officials. The surge of COVID-19 cases in recent months has placed an even higher burden on PHIs, reducing the resources available for regular investigations of factories. Meanwhile, the Department of Labour officials may possess more resources, but lack the technical expertise to examine public health guidelines. Consequently, the government must align both the Department of Labour and the Ministry of Health to find effective and efficient solutions for the medium term.

Impact on Workers

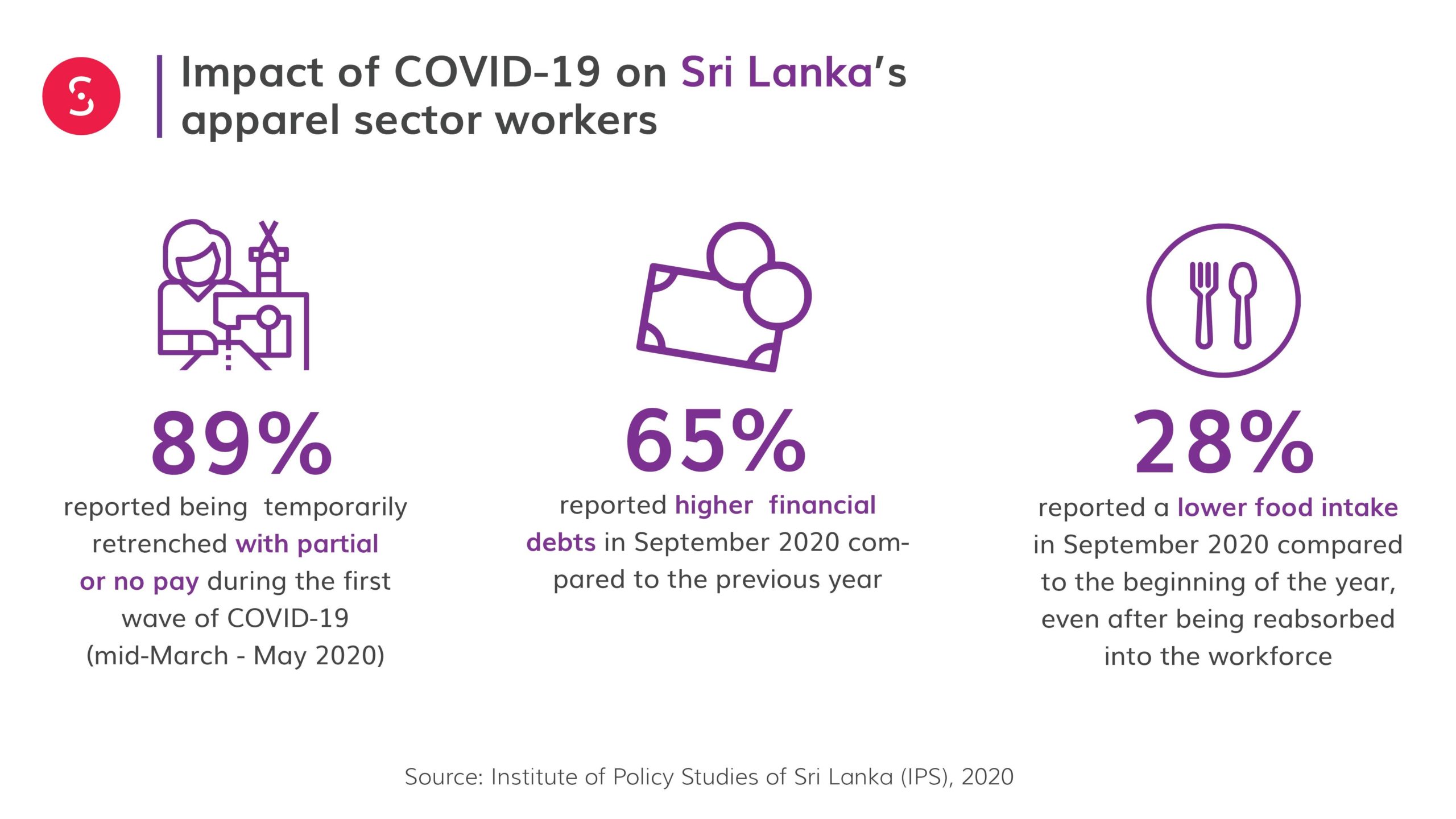

The consequences of disruptions to the apparel sector have reached far beyond merely a loss of export revenue. In a survey conducted by the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) for a study funded through a Southern Voice grant, 89% of Sri Lankan apparel sector factory workers reported being temporarily retrenched, with partial or no pay during the first wave of COVID-19 (mid-March – May 2020). 65% reported higher financial debts in September 2020 compared to the previous year. Similarly, 28% of those surveyed reported a lower food intake in September 2020 than at the beginning of the year, even after being reabsorbed into the workforce. While this sample is not representative of the entire apparel workforce, it is indicative of the growing challenges faced by both employers and employees in the sector.

The continued spread of COVID-19 through the second wave since October 2020 has led to regular lockdowns and outbreaks within factories. As a result, the Sri Lankan apparel sector continues to face disruptions to its operations. Meanwhile, its competitors in the region appear to have returned to more stable functions. This situation is hampering Sri Lanka’s competitiveness in the global apparel supply chain.

Continued interruptions affect workers’ perceptions of job security as well. Concerns over job security in Sri Lanka amongst apparel sector factory workers between April and September 2020 remained largely unchanged. But since the emergence of the second wave and its association with an apparel sector-based COVID outburst, the social stigma of workers in the industry increased significantly. With it, their confidence over job security shrunk.

Mitigating the aftershock

The apparel industry is likely to continue facing considerable challenges with frequent disturbances to its supply chains, uncertainty in future demand, and frequent lockdowns in factory areas. Such disruptions increase the burden on employees. Workers in the apparel sector are especially vulnerable to external shocks. The 2008 financial crisis, the removal of EU GSP+ benefits to Sri Lanka in 2010, and now the pandemic, attest to that.

It is becoming increasingly important to create an adequate insurance scheme for workers. Such a system would mitigate the harms of shocks to the industry on their livelihoods. It is crucial for female employees, who represent the majority of apparel sector workers. They disproportionately feel impacts on the sectoral labour force. Their job losses have dire consequences for entire families.

It is unlikely that the Sri Lankan population gets fully immunised against COVID-19 until at least the end of 2021. Hence, the government should streamline its regulatory processes to improve coordination between the Department of Labour and the Ministry of Health. It would create a more coherent and efficient mechanism to ensure workplace safety. As the industry manages a plethora of challenges, both government and private sector must adjust and adapt to safeguard the wellbeing of the industry’s workforce, both short- and long-term.