This policy brief examines the challenges governments encountered in delivering inclusive digital public services, notably in the Global South, where…

This article was originally published by IPS-Talking Economics.

This year, the United Nations marks International Women’s Day with the theme “DigitALL: Innovation and technology for gender equality”, focusing on the digital gender gap’s impact on widening socio-economic inequalities.

Technology plays an important role in modern society. It connects, innovates, and transforms economies and societies at large. Yet, women and girls continue to have limited access to technology. This gender bias is also present in Sri Lanka, where women comprise of over 50% of the population.

Digital Gender Divide

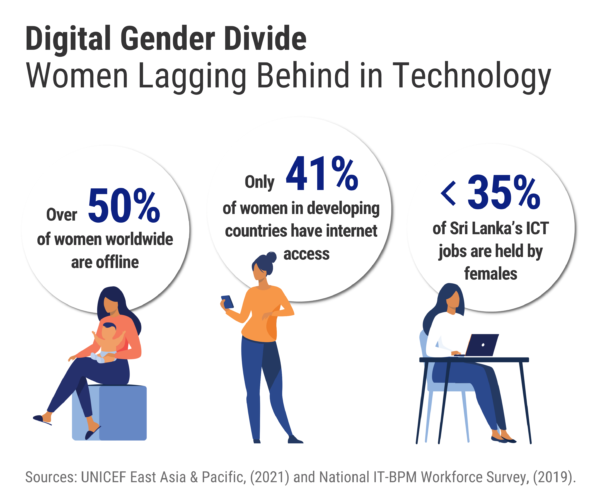

The term digital gender divide refers to the gap in digital adoption and use across genders. Findings suggest that more than half of all women worldwide are offline. The gender gap in digital access is wider across developing countries, where the internet penetration rate is 53% and 41% for adult men and women respectively.

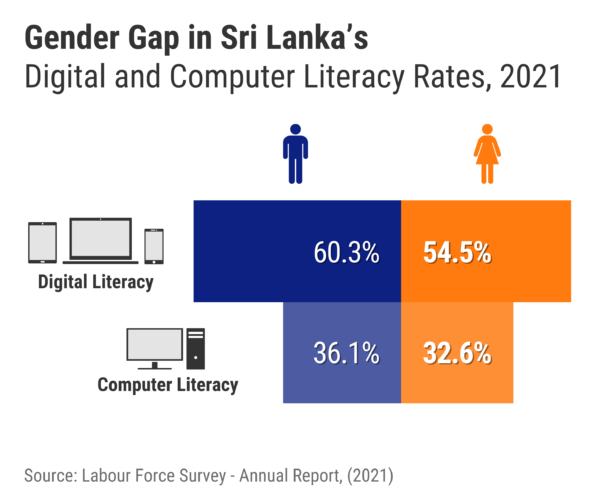

COVID-19 emphasised the importance of technology as many government services, education, business, and financial services were performed online during this time. It also confirmed that many groups not only lack access to the digital economy but also resources, technology, and knowledge. In Sri Lanka, only one out of five households owned a desktop or laptop computer in 2021. Less than half of the population used the internet, and email users were even fewer. While Sri Lanka reported a digital literacy rate of 57.2% in 2021, the computer literacy rate was only 34.3%, with females falling behind in both aspects (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Digital and Computer Literacy Rates, 2021

Although Sri Lanka’s higher rate of digital literacy comes across as a positive indicator, it is important to note that the measure for digital literacy is an individual’s ability to ‘use a computer, laptop, tablet or smartphone on his/her own.’ However, this measure may not fully reflect true digital literacy as it can also include those who only use smartphones for voice calls. Even against this measure, it is evident that women are underrepresented.

The digital gender divide adversely impacts women’s access to education, health, and financial inclusion. Women and girls face various obstacles, including the limited availability, knowledge, and socio-cultural barriers, which prevent them from fully utilising digital resources. Another deterrent is the high costs associated with digital devices and internet services, especially for rural households. Sri Lanka’s rural and estate sectors lag in digital and computer literacy in comparison to the urban sector. This is likely to have a more significant impact on girls and women in these regions. Further, digital safety concerns relating to cybercrimes, online harassment, greater potential for hate speech, and the overall lack of accountability for such actions discourage some women from using technology entirely.

Closing the Gap

Enhancing Employability Prospects – In today’s growing digital era, the absence of digital literacy and usage will reduce women’s employability prospects further widening gender inequalities. Hence addressing it is crucial to narrowing economic and social inequalities. As the job market shifts towards highly skilled positions, women must adapt and prepare to remain competitive. It can be expected that these jobs will increase more formal employment opportunities and secure forms of income generation. Currently, only 34% of ICT jobs in Sri Lanka are held by females. Increasing female representation the sector will also contribute towards having more role models for girls interested in pursuing similar fields in the future. Thus, shattering the glass ceiling requires immediate action to close the digital gender divide in the long run.

Gender Equality at Work – To address the existing gender bias, policymakers and organisations must work together to establish ‘female-friendly’ policies and programmes. Making women feel welcome and empowered is a good starting point. While addressing gender stereotypes is important, they also need to be coupled with other facilities such as safe transport and flexible work schedules to encourage more women to apply for positions in male dominated fields. This would not only increase the number of women in the field but also help women receive family support to pursue careers in technology.

Empowering Rural Women – It is necessary to provide equal opportunities for women in tech and allow them to grow so that their success can inspire other women to follow suit. This also includes bridging the urban-rural divide in technology access. Hence introducing rural women to digital technology, formal banking and digital financial solutions is important. This could also include specialised training and loan schemes for females interested in entering the technology field. Improving women’s access opens up opportunities for secure financing and a path out of poverty -by engaging in various businesses, especially at a time when e-commerce is popular. These positive economic outcomes can be a game changer for rural female-headed households and Sri Lanka as a whole. Moreover, they can provide small businesses access to international markets if done correctly.

Skill Improvements – Survey findings link higher educational attainment and knowledge in English to greater computer literacy in Sri Lanka. Thus, promoting higher education and English literacy among girls from a young age will prove mutually beneficial in improving computer literacy rates. While ICT is included in the current school curriculum, what is taught at the mandatory level is inadequate. Therefore, it is essential that policymakers update the subject matter to meet the growing digital demand. In line with this, disparities in resource allocations at the school level must also be addressed (such as inadequate availability of computers in smaller schools, absence of computer labs etc.). Encouraging girls to pursue Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM) is critical because ‘there won’t be any women in tech without girls in STEM.’

Given Sri Lanka’s current economic standing, it is also important to consider resource allocations. This is especially concerning allocating funds towards distributing computers to less-developed schools, organising training programs for rural women etc. While these are essential measures in bridging the digital gender gap, implementing any initiatives in stages is best. This will provide a better mechanism to monitor the impact of actions on closing the gap and help adjust course as necessary, without unnecessary waste of scarce resources.