Men may make up the bulk of members of violent extremist (VE) groups around the world. But increasingly, women are playing significant roles in these organizations globally and across Africa. It is pivotal to understand the dimensions of women’s involvement in VE and the radicalization that leads them to join terrorism. This insight can help African governments and relevant non-governmental organizations design a comprehensive approach for dealing with emerging threats. Policies and programmes intended to tackle VE often lack a gender-based analysis. As a result, they fail to see gender differences in the opportunities, constraints, power structures, and drivers of VE. This negligence hampers progress towards achieving sustainable development goal (SDG) 5 on gender equality and SDG 16 on peace, justice and strong institutions, particularly targets 16.1, 16.7 and 16.A.

Gender-differentiated roles within Violent Extremist groups

Existing studies suggest that stereotypical norms around masculinity or femininity (that define a “true man” or a “good woman”) play a role in men and women’s engagement in VE. In many VE groups, men are often the chief players in leadership, combat and operational parts. They are usually more outspoken and visible, holding extremist tendencies. On the other hand, women are wrongly thought to play only passive roles, as “victims, helpless, subordinate and concerned family members”.

However, the Council of Europe’s Counter-Terrorism Committee indicates that women play diverse voluntary roles in VE groups. They range from state-building to recruitment and militant tasks. State-building roles involve active operational tasks around caretaking, teaching, health service, and logistical duties. Recruitment roles cover enrolling other women to join the group. They are also in charge of spreading propaganda and giving guidance on how to navigate family objection to recruitment. Militant roles involve active combat roles, such as suicide bombing. A study on the women of the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL or Daesh) corroborates the existence of these diverse roles. ISIL/Daesh women fulfil active functions as recruiters, caretakers (including raising and indoctrinating the children of fighters) and propagandists. The study reported substantial levels of brutality perpetrated by women against women who did not comply with the group’s moral codes.

The roles of women in African Violent Extremist clusters

In Africa, however, women’s role in VE have differed across organizations. Some VE groups have used only male suicide bombers so far, although this could change. Such is the case of the Group for the Support of Islam and Muslims (JNIM) operating across the Sahel region. JNIM, formed in March 2017, is a merger of four terror bodies in Mali: Ansar Dine, Katiba Macina, Al-Mourabitoun, and Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM). It maintains the doctrinal approach that women do not participate in operations or combat. In this group, women have played mainly state-building roles, such as being informants, cooks and washers.

While units like JNIM do not encourage women’s direct involvement in terrorist activities, women’s participation in deadly attacks by Boko Haram in the Lake Chad Basin region (Chad, Nigeria, Niger and Cameroon) has been well-known since the 2000s. Boko Haram began abducting women and girls in 2009, although some joined voluntarily. More than 2000 women and girls were allegedly abducted between 2014 and 2015. The goal of enlisting more women is:

- for them to serve as wives to male combatants and mothers to the future generation of fighters, ultimately encouraging more men to join;

- to demand ransom for them and use them for prisoner exchanges with the government;

- to deploy them as cheap and unsuspected combatants, given their ‘non-violent look’.

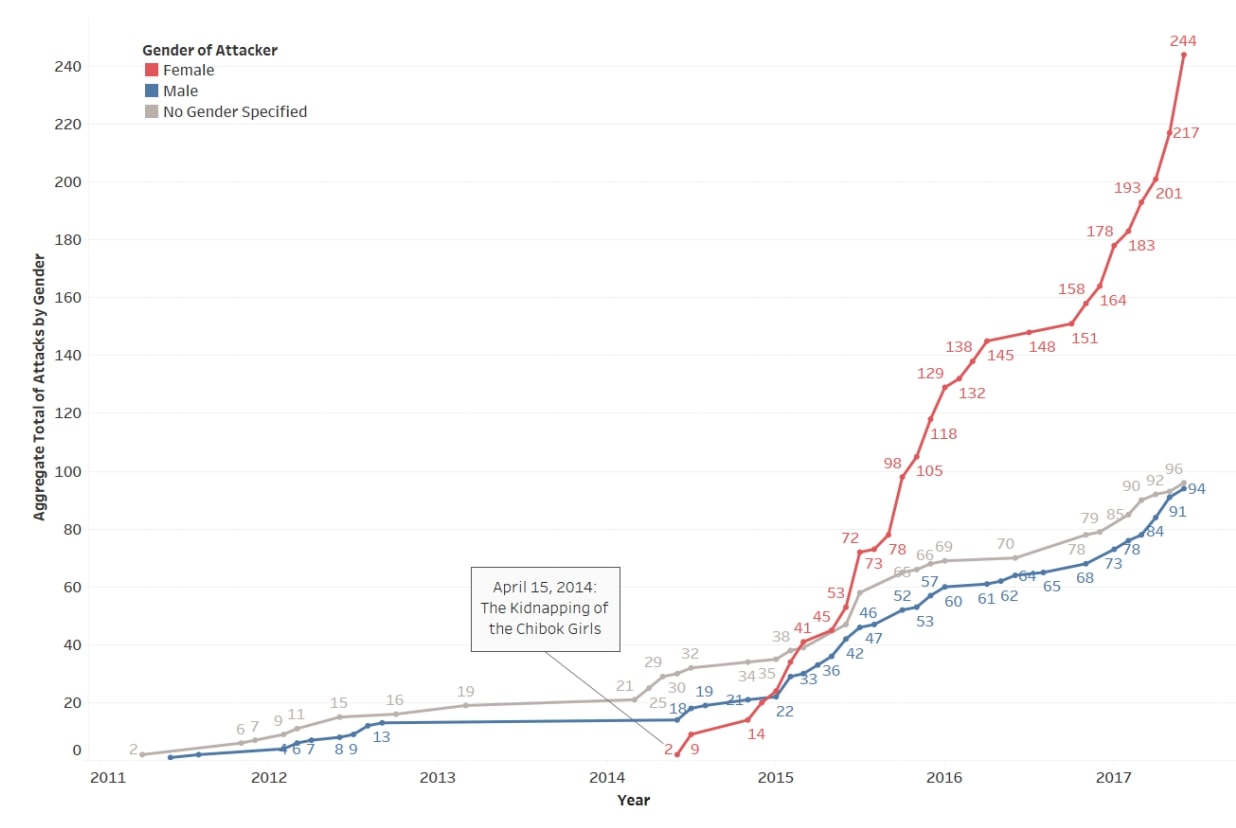

A report by Nigerian Vanguard media stated that young girls who volunteered to be suicide bombers were paid as little as 200 naira (about 60 US cents) to buy themselves food before an attack. Between April 2011 and June 2017, Boko Haram carried out at least 434 suicide attacks – of which the majority, 56%, were carried out by women. Typically, young girls and pregnant women are the “best candidates” for such attacks. Further, between January 1 and June 30 2017, a shocking 65% of the bombers were female. This number is well above the global average for women suicide bombers, which is estimated to be around 15% of most groups’ workforce (between 1985 and 2006).

Thus, unlike many VE groups in Africa, Boko Haram holds significant female membership (both coerced and voluntary). Its operational context favours the use of women in state-building and recruitment roles, but also in militant positions.

Boko Haram Suicide Bomber Attacks by Gender (April 2011-June 2017)

(Source: Combating Terrorism Centre)

Gender Considerations for Tackling Violent Extremism in Africa

- Monitor evolving mindsets in gender roles within terrorist groups: Boko Haram’s active use of female militants since 2014 signifies a departure from established gender roles, given the several benefits women combatants offer. More VE groups could change their beliefs about deploying women in combat, given the advantages. With this, they would stay ahead of counter-terrorism efforts. As such endeavours increase, VE groups could become more willing to innovate in an attempt to subvert social norms. National and regional efforts to deal with changing demographics in terrorist attacks should need strengthening.

- Address gender gaps in the security sector: The scarcity of women in the security sector in African countries, where groups like Boko Haram operate, creates a significant void. The problem starts at the most basic level, for example, with body searches. Since it is socially unacceptable for a man to conduct a ‘body search’ on a woman, females, who are deployed as unsuspected attackers, can easily pass security checks. VE organizations continue to evolve by challenging social norms and exploiting safety breaches. So, there is also a need for more women in the security sector, and for counter-terrorism strategies that consider unsuspected attackers. Changing this would be in line with SDG 5 and 16 (target 16.7) on gender equality and inclusive participation in decision-making processes at all levels.

- Adopt gender analysis in counter-terrorism policy making and implementation: The diverse and changing roles of women and girls involved in terrorist activities, as well as the differing needs of male and female members of VE groups, point to the need for gender analysis as part of policy articulation, implementation, monitoring and evaluation in counter-terrorism. It is deemed necessary to:

-

- consult women in programme design and implementation,

- carry out gender-specific research to inform programming (e.g. do the drivers of violent extremism differ for men and women? If so, how should responses change?),

- ensure gender indicators in programme implementation, monitoring and evaluation.

The matter of fact is that women are underestimated in most societies around the world. The myth that women are born nurturers and are victims or helpless family members in terrorist groups provides a dangerous loophole for terrorist organizations. If past patterns hold any predictive power, Boko Haram and other groups will continue to innovate in response to the counter-terrorism strategies/programs deployed by governments. The evolution of gender roles in VE groups plays a critical role in the portfolio of terrorist activities. Thus, program stakeholders should account for these towards promoting peaceful societies, inclusive institutions, and gender equality for sustainable development in Africa.