(re-publication from kiliza.org)

This year marks my twentieth anniversary of working in the humanitarian and development sector. It is obviously a time for reflection, not just on what I have done and hopefully achieved, but also on where the ‘aid industry’, as they call it, is heading. One of the issues I grapple most with is whether international aid is still, fundamentally, a Western construct based on assumptions that are no longer relevant, or if it is a universal form of assistance that takes different shapes depending on the region of the world we work in. In particular, if international cooperation is truly universal, is it paying more attention to what Southern citizens and the people directly affected by a crisis think of the aid they receive across the board, or is citizen engagement just another Western trend?

Let’s consider, for example, South-South Cooperation (SSC) – which I broadly define as the assistance provided by a Southern (usually upper middle-income) country to another Southern government in need of help. Having followed the main SSC debates in recent years, I have noticed that differences and similarities between SSC and ‘traditional’ aid are often based on individual perceptions, leaving plenty of questions on the role SSC plays in international development, and citizen participation in particular. Do Southern donors also want to listen to the people that receive their assistance and involve them in the decisions on the aid they get?

To find an answer, I have reached out to Senior Researcher Neissan Besharati, who is a SSC expert and Senior Researcher at the Institute for Global Dialogue, based in South Africa. He is also a member of the African chapter of the Network of Southern Think Tanks (NeST) and Southern Voice (SV) network.

Neissan, thank you for this opportunity to discuss South-South cooperation. Where do you see SSC going in the coming years?

Before answering your question, we need to first ask ourselves: what is South-South cooperation? There is an underlying assumption that we know what it is, when in fact SSC is hard to define. There is still no consensus nor agreed definition at global level. Also, current SSC debates focus on broader issues than just humanitarian and development cooperation, such as technical and scientific cooperation, cultural exchanges, arms and security partnerships, etc.

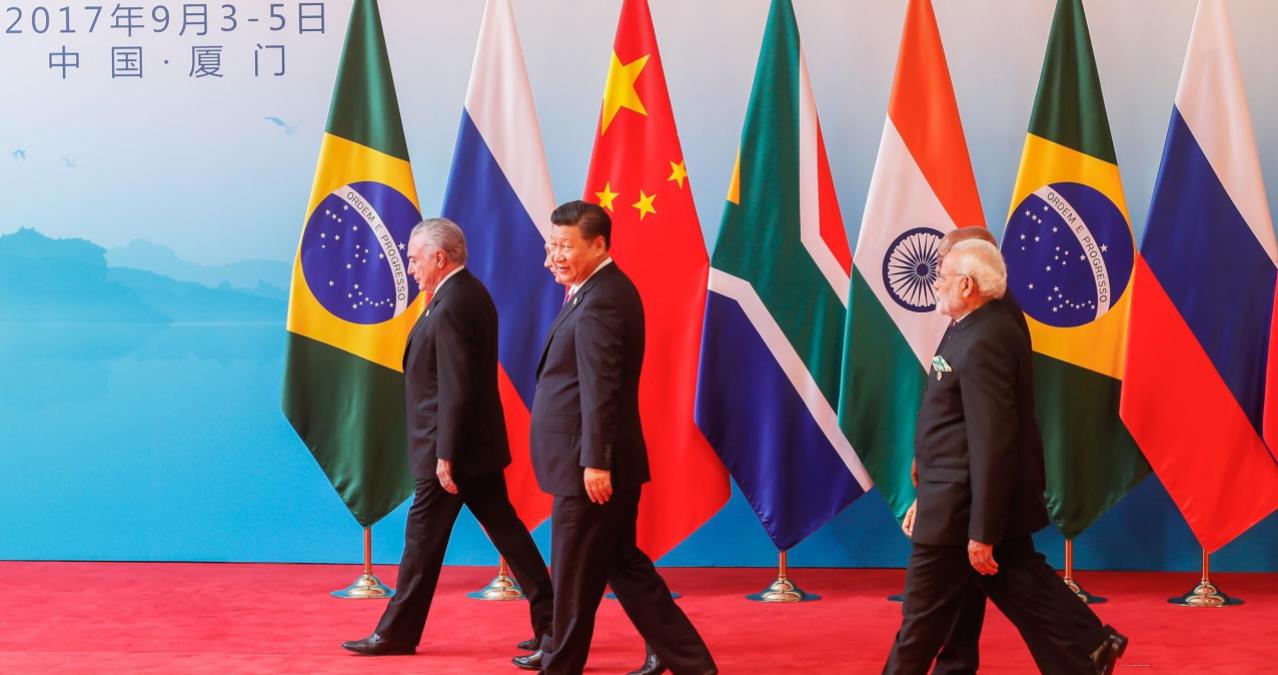

Another assumption we take for granted is that we know what a Southern country is. Here, too, we have no agreed global definitions. South of what? If it is South of the equator, does it mean that New Zealand and Australia are Southern countries too? Or Chile and Mexico, which are both members of the OECD[1], the ‘rich donor club’? Or do we mean the cooperation by BRICS countries (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), especially with Africa? It is fine to use this last definition, among many, as long as we know that we are talking only about part of a much broader picture of South-South cooperation.

Take China’s cooperation in Africa. China is the second biggest world power. Its economy continues to grow, although at a slower rate than in the past. Its cooperation will also continue to play a bigger and bigger role in Africa, in competition with traditional, North-South assistance.

How does SSC allow for citizen voice and social accountability? Are these concepts accepted or discussed by Southern donors?

It really depends on each country’s political situation. Democracies like Brazil or South Africa, for example, do allow citizen participation in the decision-making process. Usually, however, traditional SSC is still government-to-government with limited civil society engagement.

Can you provide an example of a SSC initiative or a discussion where Southern citizens have been able to influence policy-makers? What were their requests and what happened?

To continue with the previous examples, one of our civil society partners in Brazil, Articulaçao Sul, has undertaken public evaluations of Brazil’s official development cooperation. South Africa works with social movements in the Democratic Republic of Congo, as well as on people-to-people initiatives. Many of the NeST members, such as Oxfam national affiliates in Brazil, Mexico and South Africa, regularly engage in influencing their governments on international development cooperation policy.

How can Southern citizens, and organized civil society, improve SSC cooperation?

Just like Northern citizens and NGOs do with their respective donor government. It’s the same approach.

Can you share an example of SSC projects or activities carried out by Southern civil society organisations?

Yes, the South Africa Institute for International Affairs has written about cooperation between South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo, and also between Turkey and Somalia, which involve many non-State actors. Other institutions in Mexico, Brazil and India have also written about SSC initiatives involving civil society organisations.

What can the main SSC providers do to give citizens more voice, both in their own country and in the country receiving their assistance? Is there such a debate already in SSC?

In Southern provider countries, like India, we already have advanced mechanisms for engaging citizens through the creation of platforms for engagement, such as the Forum for Indian Development Cooperation (FIDC). In some recipient countries, like Malawi, there are inclusive spaces for debating and influencing government policy on development cooperation, where local NGOs can engage.

Interestingly, civic influence tends to be stronger in Southern than in Northern countries because Southern governments often lack capacity and therefore welcome civil society’s inputs. Sometimes civil society advocates are more competent than their government counterparts, even though it really depends on which country we are talking about.

What about academic institutions or think tanks like yours, the Network of Southern Think Tanks (NeST) – do you collaborate with citizens on humanitarian and/or development cooperation projects?

We need to understand that this divide between humanitarian and development aid is a construct which has evolved out of OECD discussions around the concept of international cooperation, or Official Development Assistance. For SSC providers, there is no such distinction – it’s just cooperation, whether it is for peace, governance, development or humanitarian objectives. When Haiti was struck by an earthquake in 2010, the first assistance came from countries like Brazil, Mexico and Chile. SSC often arrives more quickly than traditional, Western aid and is part of a bigger package that often includes peace-building.

As for the influence played by academia and think tanks in SSC provider countries, the picture varies from country to country, often due politics trying to divide civil society into artificial groupings. In places like China, usually only academia plays a significant influencing role.

Besides the Network of Southern Think Tanks, there are other institutions and organizations trying to mobilise citizens in the global South. For example, Southern Voice is a broader network of think tanks that reaches out to citizens in non-BRICS countries as well. Reality of Aid is a coalition of associations with regional hubs in the Philippines and Kenya, in addition to Northern countries, all monitoring the performance of aid and development cooperation.

Is there anything else you would like to say on the issue of Southern voices in SSC and/or international cooperation?

It is interesting to see how citizens are engaging with the New Development Bank, the multilateral institution set up by BRICS countries. We are still in the early days, as the Bank was established only two years ago, so it is premature to evaluate its performance. What we can already say is that we, Southern citizens, are at a much more advanced stage in engaging with the New Bank than we are with, for example, the World Bank. The BRICS countries have also already a civil society community who works together across borders to influence the policies of their governments as well as of the New Development Bank.

Thank you, Neissan. I have learned a lot about South-South cooperation and hope we can continue this conversation soon, perhaps by focusing on a specific cooperation theme.

I’m glad you found our conversation interesting. Let’s talk again soon.

[1] The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development was officially founded in 1961. Part of its original core tasks was to run the Marshall Plan in post-war Europe.