This year marks forty years of the adoption of the Buenos Aires Plan of Action (BAPA). So it is no coincidence that I have spent most of the year preoccupied with how to assess South-South cooperation (SSC). Whether this has been through field research on development finance in Malawi, or in expert meetings in Paris, Pretoria, New York and Mexico City, through papers produced for Southern Voice or academic journals – throughout this year there was one re-occurring question: how should we define, quantify, monitor and evaluate SSC?

Everyone today acknowledges the huge contribution SSC makes to sustainable development at global, regional and national level. In some instances it surpasses the role of traditional North-South Cooperation (NSC). But a challenge remains: how to identify appropriate mechanisms to monitor and account the diversity and complexity of SSC in international development.

The uneasy marriage of SSC and NSC

The Busan 4th High Level Forum saw a major effort to bring SSC into the mainstream aid effectiveness system. But the Global Partnership for Effective Development Cooperation (GPEDC) has failed to convince the big SSC providers – such as China, India and Brazil – to engage in its monitoring and accountability apparatus. SSC in fact does not sit comfortably in the assessment frameworks set out for traditional donors. Many political, institutional and technical challenges prevent SSC providers to report into the systems developed by the OECD-DAC, as myself, and other Southern scholars like Bracho and Xiaoyun have elaborated in previous papers.

Conceptual misunderstandings

To start with, SSC cannot be equalized to Official Development Assistance (ODA). SSC is not just concessional aid, it is not only for developmental purposes, and it is not always done through ‘official’ channels. On a conceptual level, SSC encompasses relations between developing countries, which go beyond grants and technical cooperation. It also includes trade, investment, infrastructure finance, peace and security, regional economic integration and other political solidarity in the global South.

After seven years of debates about these two forms of cooperation, I was pleased to hear the GPEDC Joint Support Team admit at a recent workshop in Korea that NSC and SSC are two ‘different animals’ and that they should not be compared. Although they both work towards the same objective, NSC and SSC operate in very different realms. One is not necessarily ‘better’ than the other. Representatives of OECD countries are now also voicing the same G77 mantra that “SSC is not a substitute but a complement to NSC”. The penny has finally dropped!

Growing need to measure SSC

Earlier this year in a discussion at the High Level Political Forum (HLPF) in New York, stakeholders agreed that we cannot measure SSC with the same systems, tools and approaches of NSC. It is nonetheless important to monitor SSC. This is for the sake of mutual accountability between partner countries, but also to build evidence on the contribution SSC is making towards Agenda 2030.

Assessing quality of partnerships

Different experts from the Network of Southern Think Tanks (NeST), have made substantial inroads in developing qualitative frameworks to measure effectiveness of South-South partnerships, processes and relations. Such assessment approaches use indicators derived from the SSC principles enunciated in the major historical conferences such as Bandung (1965), Buenos Aires (1978), Nairobi (2009) and Delhi (2013). Elements of such Southern evaluation frameworks can now be integrated in national and regional accountability systems. They help assess the compliance of SSC norms by SSC partners.

Quantifying and reporting SSC

Measuring quantity of SSC is certainly a more complicated affair, due to the technical and definitional challenges previously discussed. Nonetheless, great advances have been made in Latin America. Reporting of their SSC has been undertaken by the Mexican and Brazilian Cooperation Agencies, as well as the Ibero-American Secretariat (SEGIB). All these initiatives however focus primarily on technical cooperation. Capturing the contribution of trade, investment, lines of credit and other forms of economic cooperation – a major part of what China, India and other Asian partners do – is still virgin territory. Overall there is no consensus on a common definition for SSC. Having one would allow for a standardized approach to the quantification of SSC flows, that can emulate ODA as a statistical measure for the contribution by traditional donors to global development. These issues need to now be brought to the forefront during the upcoming BAPA+40 discussions in 2019.

Country-level monitoring is king!

What has become apparent in the GPEDC, but also in the UN, is that the integration of SSC in the monitoring and accountability frameworks for development cooperation is not going to happen at the global level. There is still too much North-South politics. It needs to happen at country level, where recipients are in the driving seat.

Developing countries are ultimately in charge of their national development processes and their cooperation arrangements. They decide which development partners to work with and on what terms. They are thus the only ones who can demand accountability for the support they receive from partners – whether Northern, Southern, Eastern or Western. National monitoring systems are extremely powerful, as development partners have a moral, and sometimes legal, obligation to follow the rules of the country in which they operate, making sure they align to the recipient’s development priorities and country systems.

Country-level effectiveness frameworks, at the same time, require robust domestic systems to be in place. This includes statistical, planning, implementation, budgeting, monitoring and evaluation. Institutional strengthening and capacity building in data management systems is therefore paramount. It will ensure effective monitoring and accountability of international development cooperation in recipient countries.

As we approach BAPA+40, Southern partners need to move beyond the usual political rhetoric to concrete technical proposals. Bold steps should be taken to reach consensus on reporting parameters that allow countries to define, quantify and assess the impact of SSC in national development processes and in the 2030 Agenda.

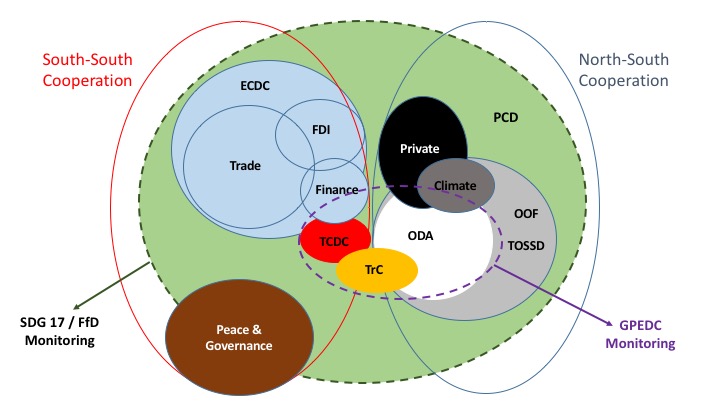

Explanation Graphic:

source: Besharati (2018), GPEDC LAP training programme, Seoul

ECDC = Economic Cooperation between Developing Countries; TCDC = Technical Cooperation between Developing Countries; TrC = Trilateral Cooperation; FDI = Foreign Direct Investment; PCD = Policy Coherence for Development; OOF = Other Official Flows; TOSSD = Total Official Support for Sustainable Development; FfD = Financing for Development; SDG = Sustainable Development Goal;

Text editor: Gabriela Keseberg Dávalos