What does the future of African agriculture look like? Will it be able to meet the demand of a population…

This article was originally published by the OECD Development Matters blog and is part of an article series collaboration between Southern Voice and OECD. This series aims to identify solutions for an equitable recovery and to sustainably address power asymmetries among and within countries and regions.

Due to gender bias and the patriarchal nature of many African economies, care work, especially unpaid, is considered a woman’s prerogative. This is often intertwined with negative social and cultural norms. In this context, is paternity leave a realistic solution to closing the gender care gap?

The Ugandan case: what law and policy do and do not address

In my country, Uganda, the article 33 of the 1995 constitution codifies equal opportunities for women in the economic, social and political spheres, so that they can realise their full potential. It states that women have the right to affirmative action to redress the imbalances created by a history of sociocultural norms that undermine their status in society. Yet, it does not provide clear strategies for reducing the unpaid care workload at home and in workplaces.

The Employment Act No. 6 (2006) section 57 determines worker rights and employer obligations, including the duty to give maternity and paternity leave. By law, mothers are entitled to 60 days working maternity leave, while fathers are entitled to paternity leave of no less than four working days a year. However, this does not prevent the workplace from giving the father a longer period.

To support the law, the National Employment Policy (2011) specifies employers’ responsibilities to provide contingencies for their workers, such as paid maternity, paternity and sick leave. This applies to both formal and informal sector workers.

Is a paternity leave realistic in Uganda?

In 2019/20, 52% of the total employed population in Uganda was in vulnerable employment. Most of them are women working in the service sector, agriculture and in low-skilled occupations. Womenearn, on average, 57 USD per month. About 94% of the working age population is employed in the informal sector, where no rules apply and maternity leave does not exist, let alone paternity leave.

The four days of paternity leave, as per Ugandan law, apply to the formal sector—in other words, less than 8% of Uganda’s employed working age population. Furthermore, there are no institutions to enforce the leave. In any case, the four days are too short to lead to care equality and most men in the formal sector rarely use them. In general, there is limited awareness of the need for and entitlement to paternity leave.

COVID-19 and care work in Uganda

During the pandemic lockdowns, care work fell disproportionally on women. Children were no longer in school and needed constant supervision. While it cannot be ruled out that men supported women in domestic work and care activities, cases were rare and mainly in urban areas.

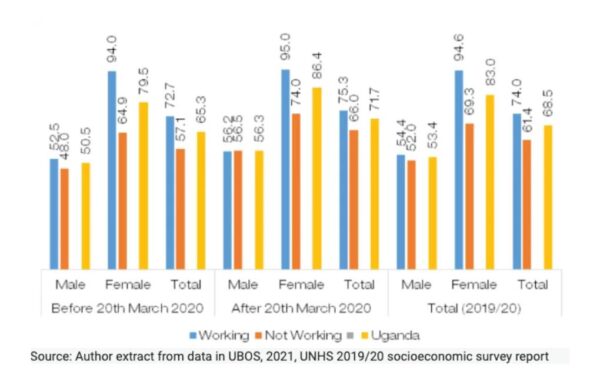

According to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, unpaid care work is high among women who work compared to those who do not, a situation that worsened during and after COVID-19 (Figure 1). The proportion of men involved in unpaid care work before and after COVID-19 remained lower than women. In total, females in Uganda spend 10 hours more on unpaid care work than their male counterparts per week.

Solution to bridging gender and care work gaps

Paternity leave for economies with high informality and institutional gaps in enforcement is unrealistic. Therefore, African governments, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa, should invest in the supply side of gender sensitive infrastructure to ease the care work burden. Such infrastructure includes early childhood development centres, play parks, public transport with priority areas for mothers and fathers with children and breastfeeding centres. These should be affordable, accessible and non-discriminatory. In the long term, they might do more for gender parity than paternity leave.